Interaction design | Dance We Must

Choreographing the user journeys through a museum exhibition with intuitive wayfinding

Role

- Exhibition designer

Scope

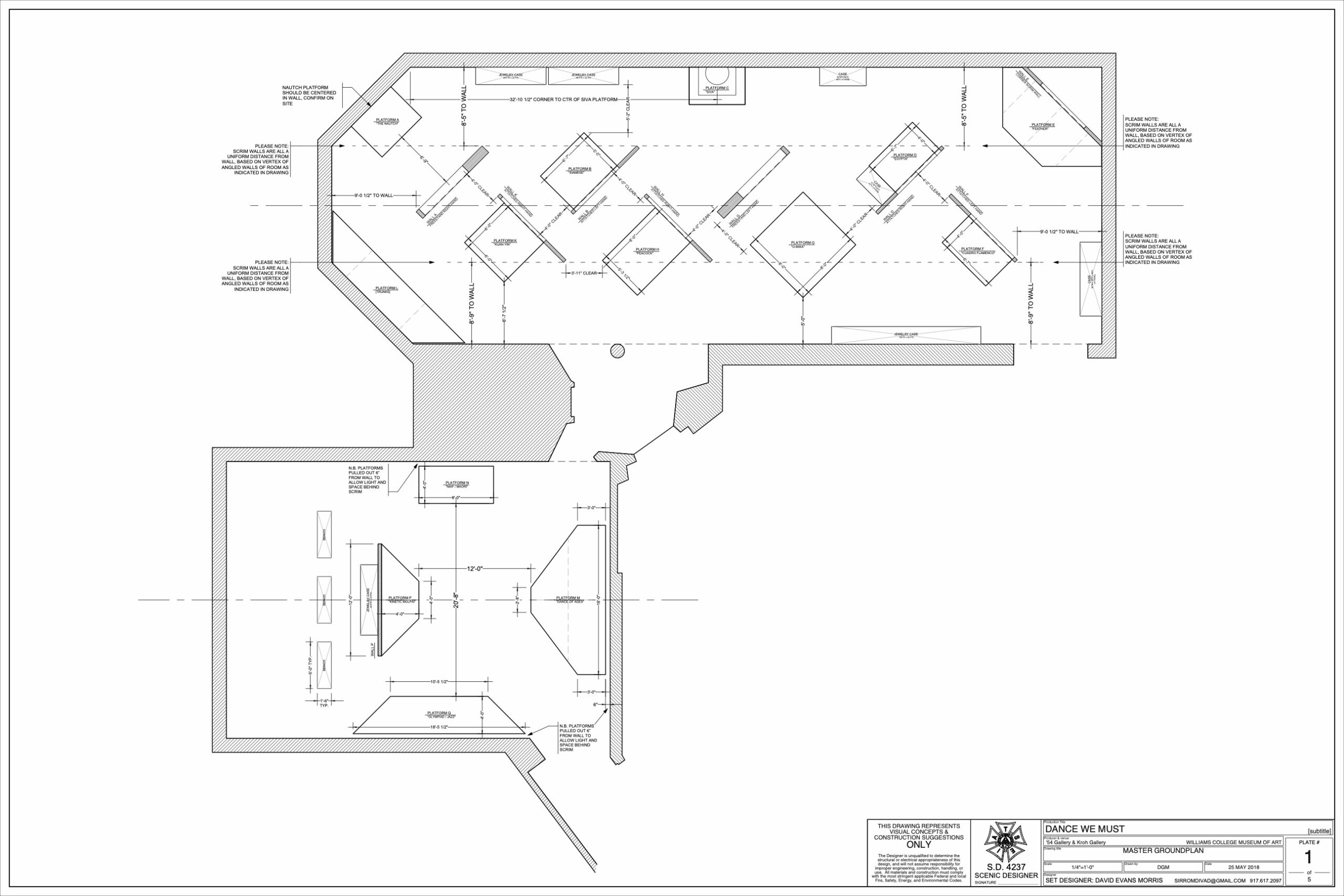

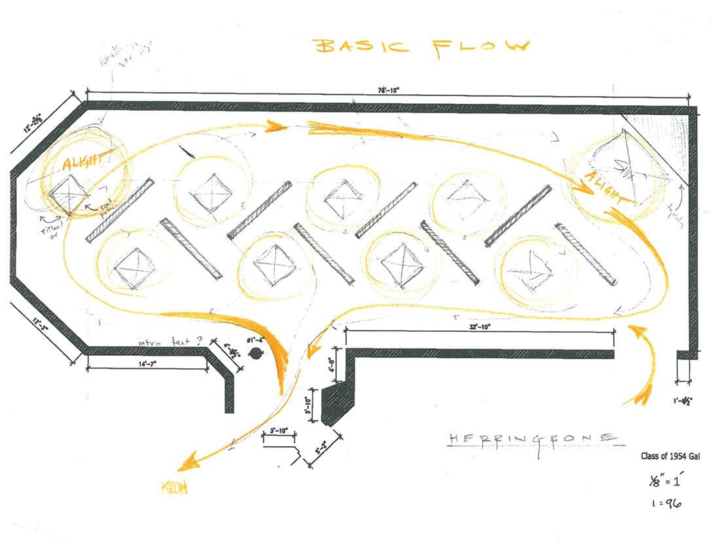

- Developed ground plans and audience flows

- Worked with curators to finalize items for display

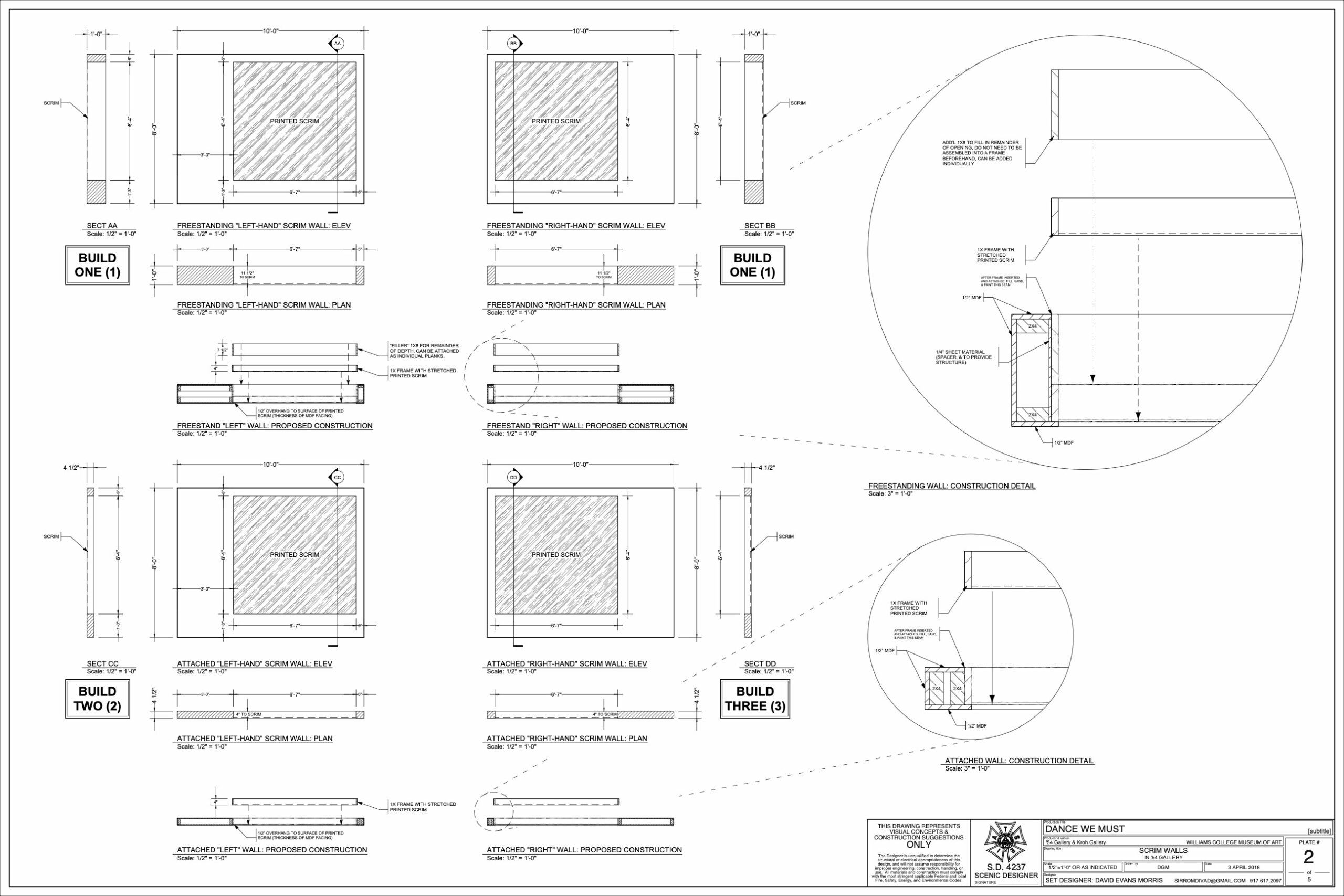

- Designed the layout of custom exhibition walls and platforms

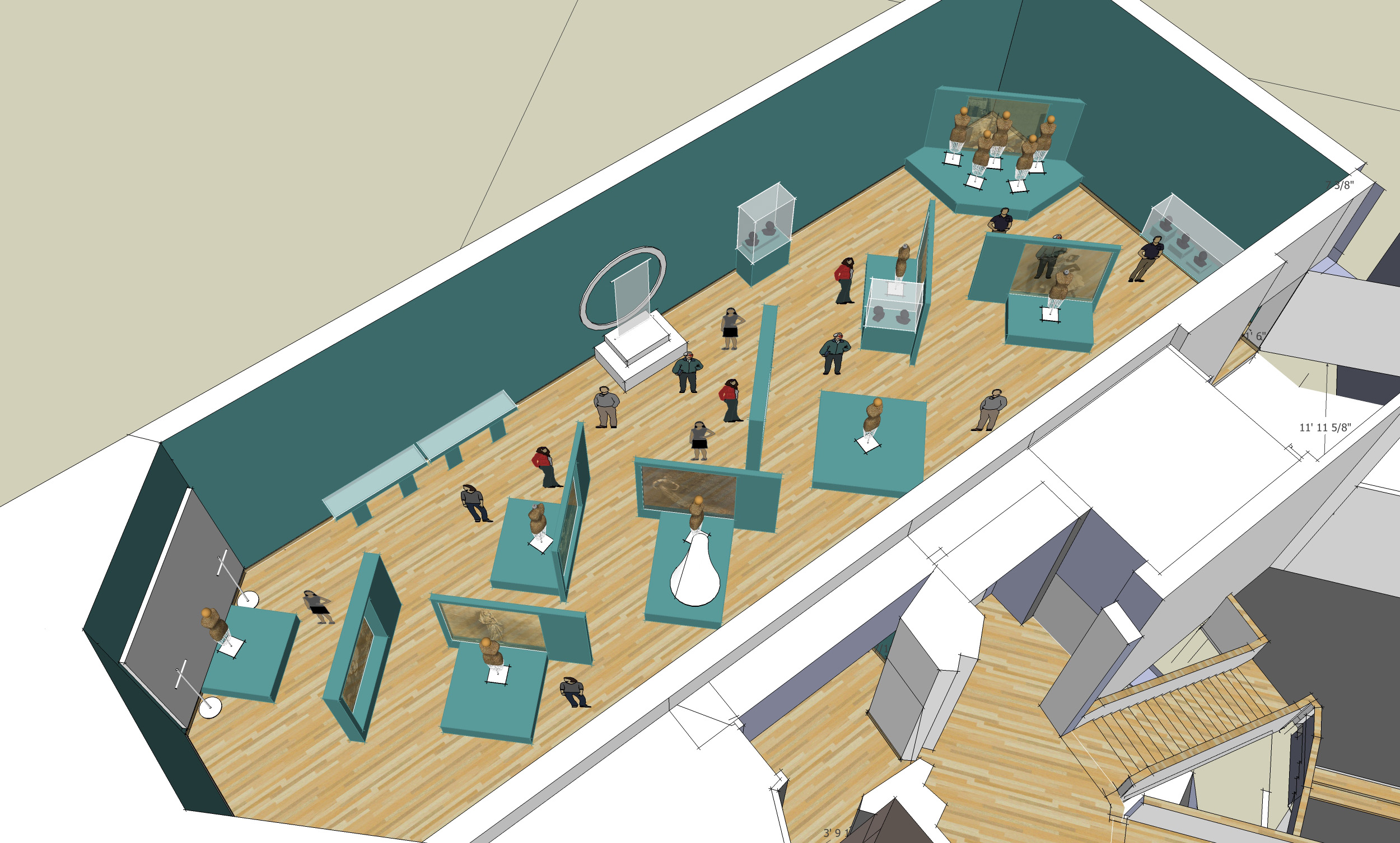

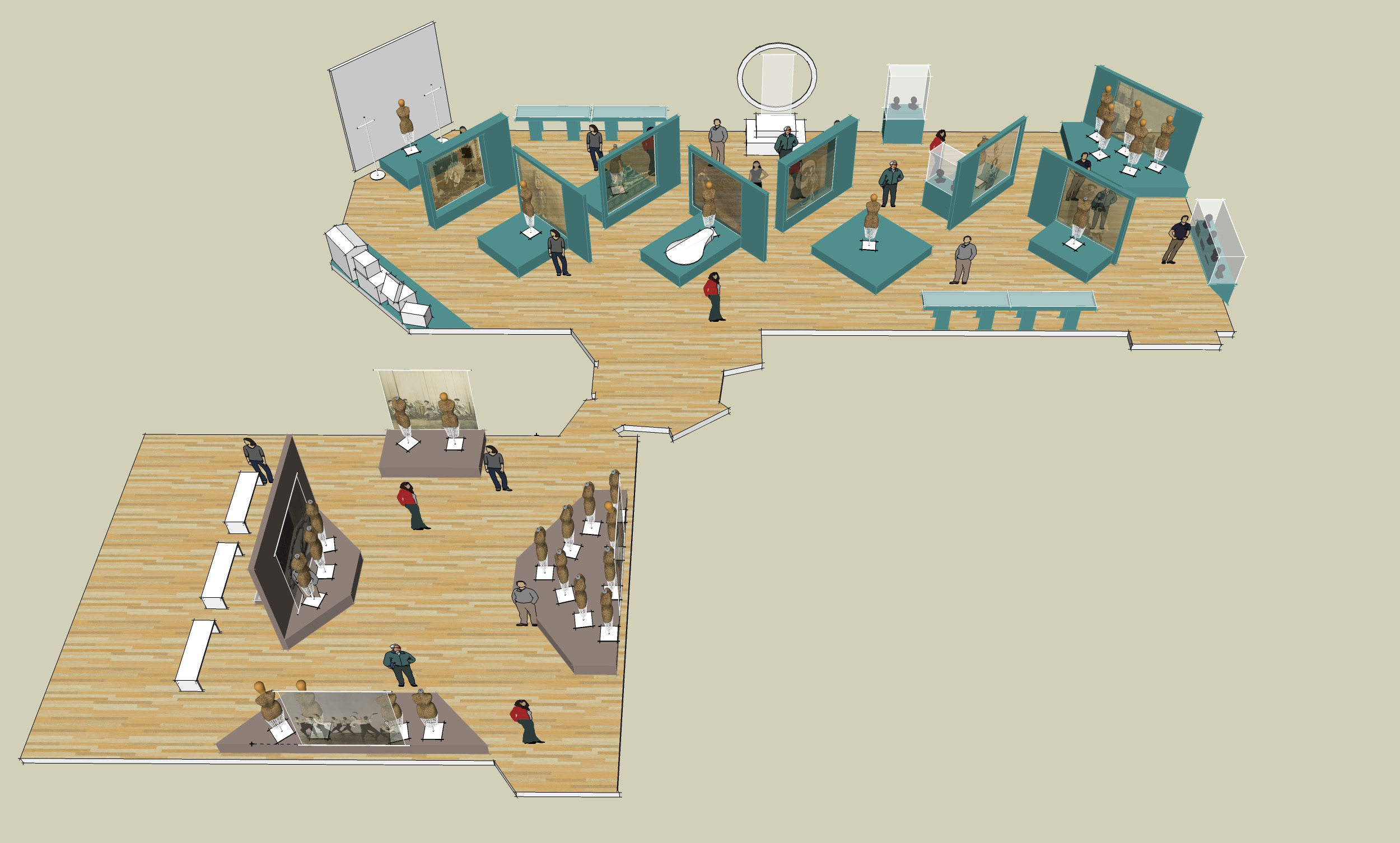

- Created and maintained 3D models during iterative design process

- Drafted built elements and worked with shop throughout construction and installation

Project Duration

- 5 months

Tools

- SketchUp

- Vectorworks

- Hand drawings (pencil & paper, Apple Pencil & iPad)

Background

The Williams College Museum of Art and Jacob’s Pillow, a dance center, theater complex, and summer festival in Western Massachusetts, were collaborating on an exhibition of more than 250 costumes, photographs, set pieces, and ephemera for one of the most important early modern dance companies in America. The exhibition would occupy two of the largest galleries in the museum, and the curators wanted to collaborate with a designer who could work with them to develop the architecture of the spaces, the narrative flow (or flows) through the objects on display, and the visual presentation of the space.

The challenge

The exhibition contained an enormous number of objects, with many of them three-dimensional objects:: costumes on mannequins or set pieces assembled in the gallery. They needed additional walls and platforms constructed to both contain and display the works and guide the audience’s movement through the exhibit’s narrative.

The solution

I created an interlocking series of niches within a large gallery space to increase display area while creating more intimate spaces for viewing the objects. The walls were pierced with large windows covered with scrim on which were printed enlarged photos of the costumes on display. This gave the subdivided space an airy feel while creating sightlines to upcoming elements, which helped pull visitors forward through the exhibit.

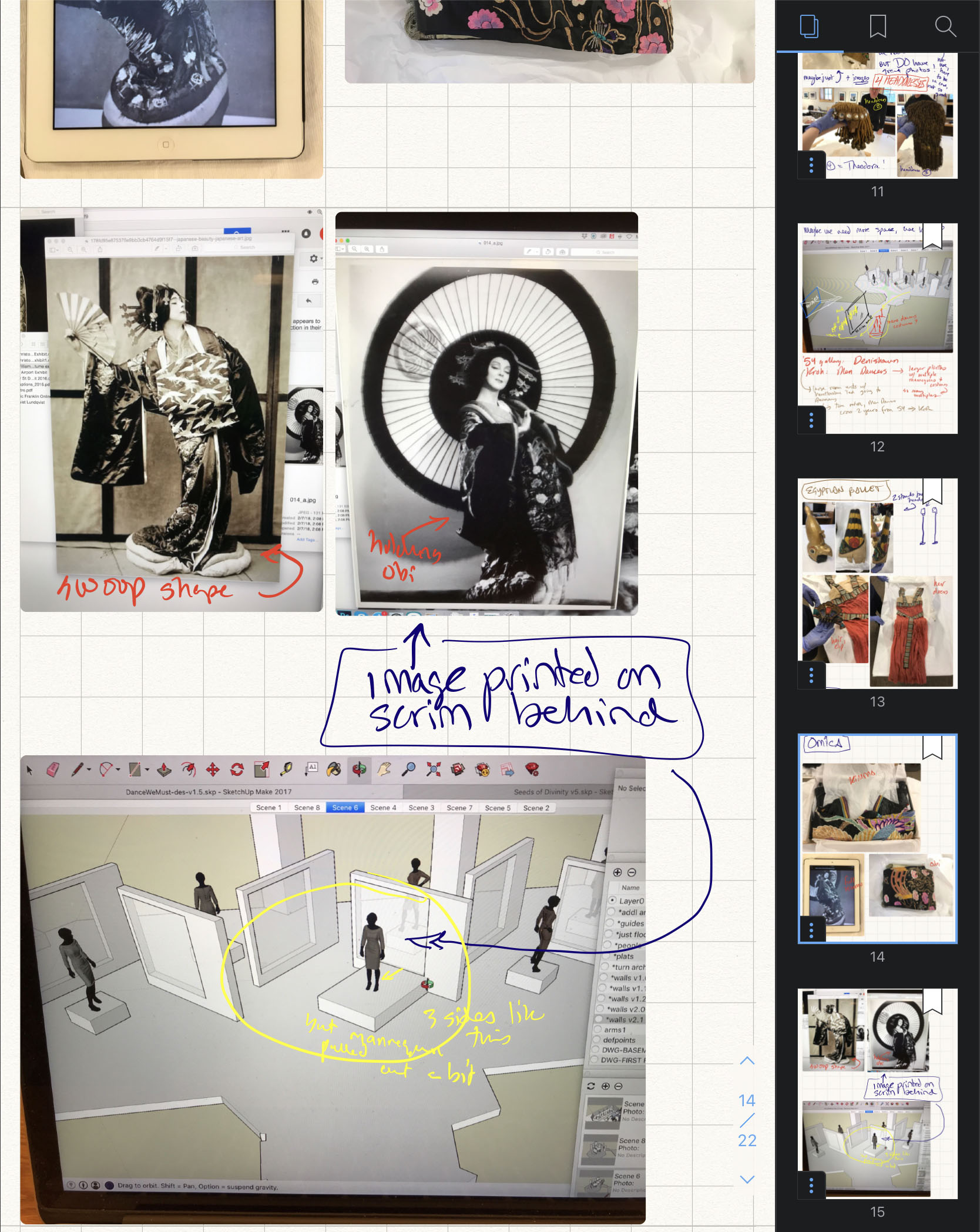

Research

The research and design processes for Dance We Must were extended and intertwined in a very productive way that allowed choices about the layout of the space and design of the visitor flows to be made in conjunction with curatorial decisions about what objects could and would be best to include in the show. These conversations began broadly (“What kind of space would best display these items?”) with some emphasis on the practical (“What are the reasonable limitations on imposed by the space?” Or: “Really, how many costumes on mannequins can we actually fit?”). But they were also wonderfully abstract and conceptual discussions about movement, narrative, and kinetic storytelling. Ultimately, my Ideas about visitor flows, sight lines, and looping paths through the exhibition deeply influenced the curators’ decisions regarding the overall narrative of the exhibit, what would be displayed, and how.

Design

The ground plan and layout for the temporary walls followed a herringbone pattern in the large gallery, with freestanding platform for costume mannequins in the center of each niche. This created a dominant movement pattern that I called “eddies and whorls”: like how rocks in a swiftly-flowing stream cause the water to swirl and spiral around them before continuing downstream, visitors would be drawn into each niche, circle around the costume piece while also observing photographs, artwork, and ephemera hung on the walls, and then spin back out into the main, clockwise flow around the gallery.

The walls were all designed to be free-standing with passable gaps between them. So while a particular flow was certainly suggested by the architecture of the space, visitors were given the opportunity to not only catch sight of objects in another part of the exhibit, but easily skip ahead and -around the room, should they so desire.

This plan changed somewhat as we continued with our explorations of the archives at Jacob’s Pillow, and also began discussions with the construction and installation teams at the museum. As we finalized the costume pieces we realized that many of them would require more space on the platform than I had initially thought when developing the “eddies and whorls” idea. This became particularly true when the conservators joined the conversation, as they had requirements for minimum distance between a visitor and object that we had to respect and support through the design. Construction-wise the costs of making so many completely free-standing walls was proving prohibitive as well, since the museum would not allow us to attach temporary walls to the floor in that gallery.

I was able to solve both problems at once by moving the mannequin platforms up against the walls. This allowed for larger platforms while retaining enough space to move around and through the niches; attaching the walls structurally to the platforms meant they were steady and freestanding without a lot of extra cost. (Two walls needed to remain freestanding and so were built extra-thick to allow for a wider base with extra weight added for support; because we only did this for two, not seven, walls our budget was able to accommodate the additional cost.)

This created a wonderful new design opportunity as well, since the costumes on mannequins would now be backed by a wall. I cut large openings in each wall which were filled with scrim printed with an enlarged period photograph of the costume being displayed in front of it. This allowed us to provide an environmental context to the costume piece, plus—since the scrim is see-through—it really opened up the sightlines through these large walls running down the center of the room, giving a lovely sense of the overall shape of the space, reminding you of pieces you’ve already seen, and permitting glimpses of what was to come.

This idea for the scrim panels also influenced the curators’ selection of costume pieces to be displayed on the mannequins, as we needed to have a period photograph of that costume (or a similar one) to enlarge and print. The scrims were quite an undertaking, and beyond designing them I also helped source the fabric and printshop for the job, scanned some of the hi-resolution images, and did all of the photoshop retouching of images and other preparations for printing. This sometimes included some elaborate image adjustments and manipulations to crop out extraneous or confusing elements and generally improve legibility of the images.

Response

DANCE WE MUST: TREASURES FROM JACOB’S PILLOW 1906-1940 opened in the summer of 2018 and was on display for six months at the Williams College Museum of Art in Williamstown, Massachusetts. As a collaboration between two significant cultural institutions in the Berkshires it was well attended to and received. The New York Times printed a long interest piece covering the upcoming exhibit. Jacob’s Pillow has a lovely article going into greater detail on the archivists' process and discoveries, and WCMA created a promotional video for which they interviewed me as one of the creators behind the exhibition:

Reflections on project

The exhibition design for Dance We Must was a high level collaboration not just between cross-functional teams within a unit, but working across units. Curators, and archivists from two museums came together with designers, scholars, and artists from the dance and theater world to think creatively about this exhibit.

My prior experience as a set designer for theater and opera had always been concerned with movement through space and kinetic storytelling. This was often centered on the bodies of actors, but could also be about actors and audience moving in and out of theatrical space together in experimental immersive performances. Collaborating with curators to design the visitor flows through an exhibit was both a familiar task, and a delightfully strange one. The autonomy of the museum visitor to craft their own narrative was an amazing opportunity for designing forking path narratives, and allowed me to think deeply about wayfinding, sightlines, and navigation.

Last pie baked:

Pear pie with an almond cake topping.

Of course it's gone now. Long gone.

©2024 David Gürçay-Morris